Why Pinduoduo’s Silence Is a Nightmare for Analysts and a Blueprint for China’s E-Commerce Dominance

Pinduoduo’s Earnings Call Circus

Every quarter, like clockwork, the financial world engages in a ritual as predictable as a Beijing traffic jam. Analysts, investors, and the terminally curious flock to the earnings call of Pinduoduo—China’s most enigmatic e-commerce giant—hoping for clarity. Instead, they receive a Rorschach test disguised as a financial update.

Pinduoduo’s earnings calls are a masterclass in saying nothing. The management responds to three or four carefully selected analysts (who dutifully raise their target price to $190 afterward - you just can’t make these things up!) by simply rereading prepared remarks. If you’re looking for hand-holding narratives, numbers to plug into your Excel spreadsheet, or AI-themed bedtime stories, you’d have better luck getting a straight answer from a Politburo spokesperson.

In case you missed it here are the numbers for Q4.

The Numbers

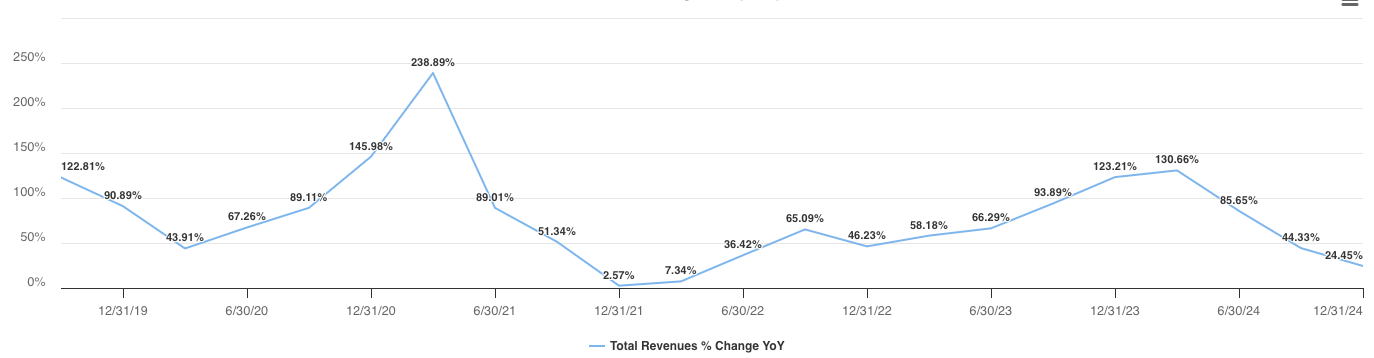

Revenue: 24% growth in Q4, online marketing revenue grew 17%, transaction services (a.k.a. Temu and Duoduo Maicai) grew 33%

Operating Profit: Up 14%.

Net Income: 18% increase.

Cash Hoard: $45.4 billion USD.#

Duoduo Maicai, you ask? For those unfamiliar with Pinduoduo’s history or operating solely from afar, this unit might as well not exist in the company’s official narrative. Duoduo Maicai is Pinduoduo’s community group-buying division—a sector that ignited a gold rush among China’s tech giants during its peak. While competitors burned billions in pursuit of dominance, only Pinduoduo (and to a lesser extent, Meituan) emerged with sustainable success. Yet the company has acknowledged Duoduo Maicai in filings just once. This is classic Pinduoduo: where others might tout such achievements, they execute and remain silent.

Pinduoduo’s strategy can be distilled to a single ethos: “We’ll occasionally disclose what we’ve done —not what we plan to do.” Founder Colin Huang’s early writings, which blend Warren Buffett’s focus on long-term value with Sun Tzu’s strategic discipline, foreshadowed this approach (see here for more details). Distractions are kryptonite. Execution is sacrosanct.

This quarter’s results—marked by a clear slowdown in revenue and profit growth—align precisely with management’s warnings from prior quarters. They had explicitly cautioned that earnings and revenue would deteriorate as investments accelerated (see here and here).

The Earnings Call

Now, let's quickly cover Pinduoduo’s latest earnings call, they sometimes reveal valuable insights if you try to really listen. Last quarter, for instance, Pinduoduo openly admitted making a significant error with government subsidies related to electronic appliance trade-ins. They acknowledged paying—and continuing to pay—a steep price for this mistake, clearly reflected in the recent earnings. Their transparency in acknowledging shortcomings is rare.

A key highlight this quarter was Pinduoduo’s increased emphasis on China's western regions, areas traditionally overlooked by other major e-commerce platforms. They now serve approximately 100 million users there, specifically highlighting efforts to deliver high-quality products.

Moreover, Pinduoduo’s strategy has noticeably shifted. Previously focused solely on customers, they're now creating a balanced ecosystem catering equally to customers and merchants. This new approach aligns with their "high-quality development" initiative, significantly boosting support for merchants.

This strategic shift is likely a direct response to earlier merchant protests outside Pinduoduo’s headquarters (yes I know it’s in Dublin but we all know it really is in Shanghai)—a topic I've previously discussed—or perhaps it's influenced by what Nobel Prize-winning economist Richard Thaler might call a government 'nudge,' though I'm not sure if nudge quite captures what you feel when the Chinese government sits you down and has the talk with you. Regardless, management seems genuinely committed to the approach now.

The core idea behind their strategy is simple: lowering platform fees and merchant operating costs. This frees up merchant capital, which can then be reinvested into product quality improvements. Better products lead to increased merchant income, creating a virtuous cycle of growth and profitability. Pinduoduo isn't alone in this method; Meituan described a similar strategy, albeit with a smaller 1 billion RMB merchant support program compared to Pinduoduo's 10 billion RMB commitment.

Management openly acknowledged that these merchant-focused investments are pressuring short-term earnings, particularly given today's challenging international environment and heightened domestic competition. They also established a dedicated committee to address merchant complaints, another indication of potential government influence.

However, compared to earlier quarters when government actions seemed to surprise them, management expressed greater confidence this time, highlighting promising early results. They explicitly stated plans to further increase these investments, and with roughly $45 billion USD in available cash, they're well-equipped financially. Exactly how they'll deploy this considerable capital remains to be seen1.

Finally, management stressed that investors shouldn't evaluate the company solely on short-term financial results. Instead, they positioned Pinduoduo as a global enterprise with broader responsibilities, actively supporting merchants, underserved regions, agriculture, and contributing positively to the wider economic and social ecosystem.

That wraps up the earnings call.

The Takeaway: Embracing the Unknowable

Pinduoduo is certainly an extreme case regarding how little they disclose, but other companies also don’t reveal the information I want—whether due to sheer size or competitive dynamics.

Take Alibaba. With its vast number of subsidiaries, a full earnings call covering each subsidiary in detail would require a 24-hour livestream and a coffee IV infusion. Segments like Lazada—once CEO Daniel Zhang’s pet project, worthy of weekly cross-country flights—now get only a single throwaway sentence. Size breeds abstraction.

Meituan’s pivot to Saudi Arabia? Without cohort data, order frequency stats, or competitive insights, evaluating it is like judging a restaurant by the color of its takeout bag. Yet this is the norm: companies disclose what they must, not what we wish2.

At some point, you either accept the fog or stay home. As scholar Richard Zeckhauser argues, investing often means dealing with the unknown and the unknowable.

Analysts, of course, hate this. Their spreadsheets demand certainty; their paychecks depend on it. But as Pinduoduo proves, sometimes the best strategy is to shut up, execute, and let the results speak.

The Analyst Farce: Spreadsheet Jockeys vs. the Oracle of Shanghai

Picture this: A roomful of MBAs (ok just metaphorically its a telephone conference after all), armed with Bloomberg terminals and a pathological need to justify their six-figure salaries, lobbing questions so boring they’d make a Party Congress press conference seem thrilling.

Take Tencent’s recent earnings call. Some brave soul asked CFO James Mitchell about the “high base” in domestic gaming revenue—a question so embarrassing you could hear Mitchell’s soul exit his body before you regained control. His reply?

I mean, I guess it's the curse of this kind of industry that if you do well, then people worry about the base effect a year later.

I don’t even know how someone could ask such a question—only analysts think like that. A business owner knows that if you have a great quarter, you happily accept it, even if it means the following year’s growth looks weaker year-over-year. Last year, my own company had a three-month stretch where we didn’t earn a single RMB. Then, in the next month, we made more than 7 times our usual monthly revenue. Do we worry about year-over-year comparisons next year? Of course not. That’s business—messy, nonlinear, and allergic to spreadsheets.

It’s the same when analysts on the last JD call asked about the “high base effect” from the government’s electronics trade-in program. How can you even ask something like that? If someone buys an air conditioner today, they’re out of the market for 20 years. Phones? Maybe three. Replacement cycles aren’t rocket science—yet analysts demand granularity anyway. If you think these programs are anything but one-off boosts, you might also believe in the tooth fairy.

I think Pinduopduo treats analysts like a nuisance—a fly to be swatted, not fed. Pinduoduo doesn’t need analysts to understand. They singularly focus on the business and want to avoid side distractions.

Here is what Colin Huang has to say about that:

Pinduoduo's survival depends on the value it creates for its users; I hope our team wakes up feeling anxious every day, never because of share price volatilities, but because of their constant fear of users departing if we are unable to anticipate and meet users' changing needs;

Pinduoduo's core value is "本分" (Ben Fen). One of the layer of meaning is

Insulate our minds from outside pressures so that we can focus on the very simple basics of what we should be doing;

Being the living nightmare of an analyst—not feeding their spreadsheets, saying nothing, making investors feel uneasy or even suspicious—is, of course, a suboptimal setup for high stock prices. In the following, I’ll share how I think about this. More importantly, I’ll try to explain some new developments Pinduoduo doesn’t talk about, and why they do certain things the way they do.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Great Wall Street - Investing in China to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.